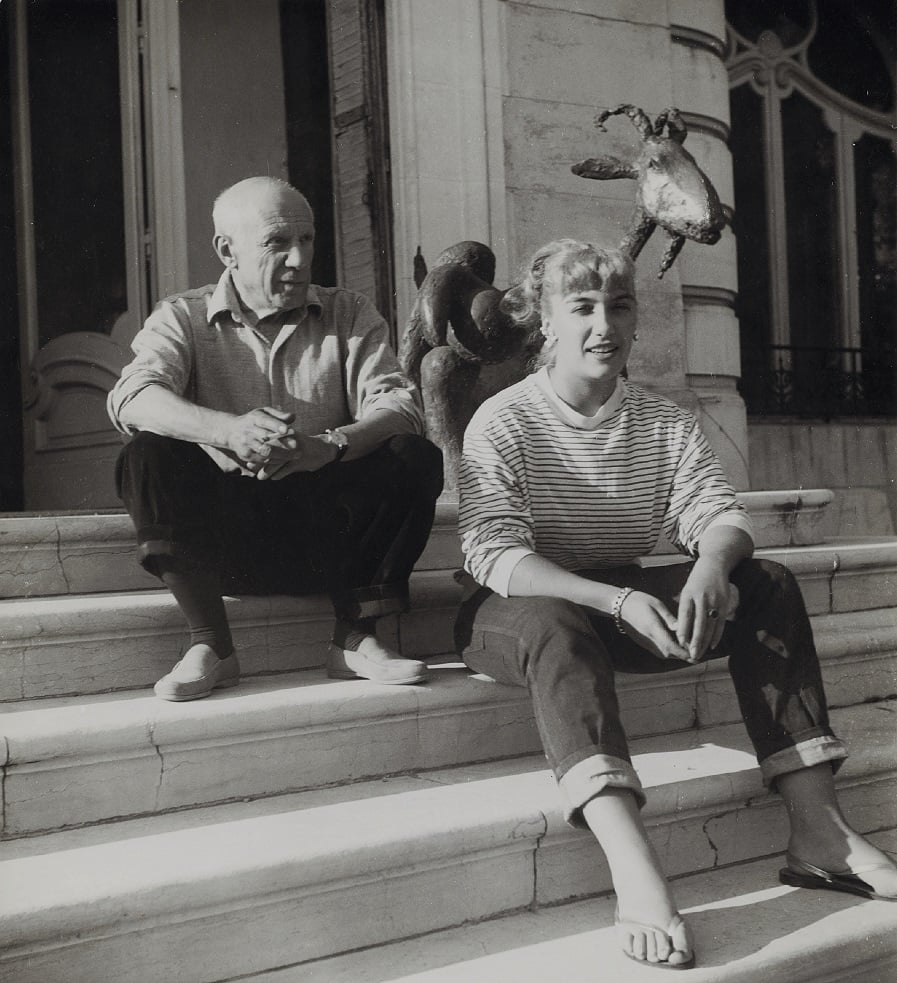

Diana Widmaier-Picasso interviews her mother, Maya, about growing up with the great artist.

In the following interview, excerpted from the new book Maya Ruiz-Picasso, Daughter of Pablo, Diana Widmaier-Picasso interviews her mother, Maya Ruiz-Picasso, about her early life as the great artist’s first child.

Yes, it was in the 1940s. I liked telling people that my father was a housepainter, even though everyone knew who Picasso was at the time, but often considered him a fraud, a charlatan.

What was your relationship with the people around your father: the artists, his dealers, and the artisans in Vallauris?

I was very close to Braque and his wife, Marcelle; I thought of him as my uncle. I also saw Miró often, whom my father liked a lot. I was also very fond of André Breton and I’m still friends with his daughter, Aube.

Ambroise Vollard died when I was four years old, so I don’t really remember him. But my mother told me I often slept in his arms. He let us stay with my father in his home in Le Tremblay-sur-Mauldre, 40 kilometers outside Paris. My mother and I lived there from the fall of 1936 until the war, and my father would join us there on weekends. My grandmother, Jaime Sabartés, and his wife, Mercedes, were living with us, as was the driver Marcel Boudin. I knew Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler better, but I only met Paul Rosenberg once, when I was 20. I also met Brassaï, and then Matisse when I was 15; he was very old at the time and died a few years later, in 1954.

Pablo Picasso, Maya à la poupée [Maya with a Doll], Paris, January 16, 1938. Musée National Picasso-Paris © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée National Picasso-Paris) / Adrien Didierjean.

Max Pellequer was my father’s friend, adviser, and banker. He managed his expenses and paid his bills. I would also often see his brother Raoul, who was in the office next door. Every Thursday, I would go with my father to the safe at the BNCI [now BNP Paribas], at 16 Boulevard des Italiens. This is where the safe was, in a room five by three meters big. My father often said, “You have to live modestly and have lots of money in your pocket.” He was thrifty, but he wasn’t really aware of what he had and would let his work pile up in all his studios.

[…]

Picasso made small toys for you during the war. How did he make them?

I had only a few toys at the time. He made paintings for dollhouses out of matchboxes. He made me paper theaters, characters, and animals, and told me stories while he made the animals move with little tabs. He also had fabricated for me a family of small characters in fabric with heads made of chickpeas.

You’re particularly fond of the still lifes Picasso made during the war. What interests you most about that work?

The still lifes are sometimes overlooked, wrongfully so. Yet they convey the general atmosphere of a particular time. Through simple colors recreated on canvas, we could dream of cherries or the end of the war and fear. Still lifes above all transmit the moods of painters. For example, my father loved plump flowers and plants, some in orange and yellow tones, colors reminiscent of Spain.

Picasso had a special relationship to inanimate things, to objects. He kept everything—palettes, shoes, and even nail clippings and hair. How do you interpret this habit? Did it have something to do with beliefs, with the fear of being forgotten, or some kind of memory ritual?

My father gave me his nail clippings because he was very frightened that people would use them against him. He was afraid that someone, anyone, would take them and cast some kind of spell. He gave them to my mother or to me, because he knew that we loved him and we weren’t going to cast a spell on him.

Pablo Picasso, Personnage [Figure] Mougins, March–April 1938. Private collection © Succession Picasso, 2022 © Private collection / Photo Zarko Vijatovic.

After I was born it became a habit. I was the flesh of his flesh, I looked terribly like him, and nothing could happen to us, to him or to me.

Did Picasso talk to you about religion?

Never. But he told me about his baptism. My mother had medallions and photographs of Jesus, the ones they made for first communions and baptisms. She had great respect for “photos du Bon Dieu,” as she called them.

You wrote to [Picasso biographer] Pierre Daix after his death. Is that because you’re a believer?

No. I’ve always written after the death of people I love, after the death of my photographer friend André Villers too. It’s more a form of mysticism, in fact. He thought I came from another planet because I knew a lot of things.

The name you were given at birth has religious connotations: “María de la Concepción.” We find it written by Picasso in your exercise books. Do you know where this given name comes from and who chose it?

At my birth, the last thing my parents were expecting was a girl. The first name that came to mind was that of my father’s sister, Conchita, the diminutive of Concepción, who died of diphtheria at age seven. He had vowed to God to stop painting and drawing if his sister was spared. He interpreted this event as a divine sign which impelled him to make art and stop believing in God. Because I couldn’t pronounce my given name, they opted for “Maya,” which means so many things: the biggest cosmic illusion in Sanskrit, the Mayas of Central America … And yet it took me nearly 60 years to gain the right to call myself Maya under French law. And so I was born twice, if not three times.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait de Maya de profil [Portrait of Maya in Profile], Paris, August 29, 1943. Private collection © Succession Picasso, 2022 © Private collection / Photo Zarko Vijatovic.

One day, my father told me, “This is your brother.” I was 10 years old, it was after the war in Paris. I remember he rode a motorcycle and would take me in his sidecar. We would joke around a lot. He was very proud to have such a beautiful and intelligent little sister! [Laughs]

When Marcel Boudin left, Paulo drove my father for several years. Marcel had served as my father’s driver since 1934. At the time, he drove my father and mother from Paris to the Château de Boisgeloup.

Did you know Olga, Paulo’s mother?

Yes, I met her briefly. I was 12 at the time and I was at Paulo’s place, repainting his new apartment. She came with cakes and toys for her grandchildren. That was the first time I saw her. I could sense that the relationship with my father was difficult. They didn’t even use his given name.

I saw Marina [Paulo’s daughter and Olga and Picasso’s granddaughter] as a baby, and my mother brought her to my father. She said, “Here, this is your granddaughter.” She took Marina to him, she was in her swaddling clothes. In fact that’s why Marina always said that my mother was a bit like her grandmother.

What was your experience of Picasso’s relationship with Dora Maar?

I was still a child, but I met her several times. She was the complete opposite of my mother, who was blond and calm, whereas Dora Maar was a brunette with a strong temperament. Relations with my mother were difficult. Dora wasn’t able to have children and she must have suffered from that. My father did everything he could to keep them from meeting. Dora would come to the Grands-Augustins studio in the morning or late in the evening and we went there in the afternoon to get logs of wood and coal nuts for our stove. One day we turned up and she was there, standing next to Guernica. I could sense that my father was ill at ease and my mother was tense. I was five years old. I started crying and I said to my father: “I don’t want to see the dribbly lady.” I was talking about Dora Maar, who licked her lips a lot. I never saw her again. Another time, my mother realized that he was giving them the same dresses by Jacques Heim. She went round to see Dora Maar, who lived in the Rue de Savoie, because there was a delivery mistake. That led to a pretty stormy exchange.

Excerpted from Maya Ruiz-Picasso, Daughter of Pablo, published by SKIRA Editore, edited by Émilia Philippot and Diana Widmaier-Ruiz-Picasso. (Published on the occasion of the exhibition “Maya Ruiz-Picasso, Daughter of Pablo,” shown at Musée National Picasso-Paris thru Dec 31, 2022.)